The federal government on Tuesday charged a major drug distributor — for the first time — for its role in perpetuating the country’s deadly opioid epidemic.

Rochester Drug Cooperative faces charges for conspiring to distribute drugs and defrauding the federal government — after the company didn’t report thousands of suspicious orders of opioids, including oxycodone and fentanyl. Rochester is the sixth-largest distributor in the US, according to the New York Times.

The company, which as a distributor essentially links opioid makers and pharmacies, effectively admitted to committing the crimes it’s accused of in court on Tuesday.

“We made mistakes,” Jeff Eller, a Rochester spokesperson, said in a statement, according to the Times, “and RDC understands that these mistakes, directed by former management, have serious consequences.”

Separately, former chief executive Laurence Doud and former chief of compliance William Pietruszewski were reportedly charged, the Times reported.

According to the Times, the Drug Enforcement Administration investigated Rochester for two years, after the company violated terms of a previous civil settlement over opioids.

This is not the first time a drug distributor has faced serious legal consequences from the opioid crisis, with companies like Cardinal Health, CVS, McKesson, and Walgreens paying tens of millions of dollars in fines related to the opioid epidemic in recent years. But this is the first time a distributor has faced federal criminal charges, similar to those filed against illicit drug dealers and traffickers.

The news of the charges comes as opioid makers and distributors face increasing legal consequences — in the forms of lawsuits, fines, and charges — for their involvement in today’s drug overdose crisis, which is the deadliest in US history.

Hundreds of lawsuits have now been filed against the companies. Several states are suing individually, and Oklahoma recently landed a legal settlement. A separate collection of about 1,600 lawsuits, largely from various levels of government, has been consolidated by a federal judge in Cleveland in an attempt to reach a landmark legal resolution to the opioid epidemic.

Since 1999, more than 700,000 people in the US have died of drug overdoses, mostly driven by an increase in opioid-related deaths. That’s comparable to the number of people who currently live in big cities like Denver and Washington, DC. Some estimates predict that hundreds of thousands more could die in the next decade of opioid overdoses alone.

The hope of the legal action against opioid makers and producers is not just to hold them accountable, which alone could help deter drug companies from misbehaving in the future, but also to get funds — whether through fines or other legal payouts — that could be used to pay for addiction treatment. Addiction treatment is notoriously underfunded in the US, with experts in recent years calling on the federal government to invest tens of billions of dollars in building up treatment infrastructure. (For reference, a 2017 study from the White House Council of Economic Advisers linked a year of the opioid crisis to $500 billion in economic losses.)

Since companies like Rochester helped cause the opioid crisis, advocates argue that they should help pay for the consequences of the epidemic.

How opioid makers and distributors helped cause the opioid epidemic

The opioid epidemic can be understood in three waves. In the first wave, starting in the late 1990s and early 2000s, doctors prescribed a lot of opioid painkillers. That caused the drugs to proliferate to widespread misuse and addiction — among not just patients but also friends and family of patients, teens who took the drugs from their parents’ medicine cabinets, and people who bought excess pills from the black market.

A second wave of drug overdoses took off in the 2000s when heroin flooded the illicit market, as drug dealers and traffickers took advantage of a new population of people who used opioids but either lost access to painkillers or simply sought a better, cheaper high. And in recent years, the US has seen a third wave, as illicit fentanyls offer an even more potent, cheaper — and deadlier — alternative to heroin.

It’s the first wave that really kicked off the opioid crisis — and where opioid makers and distributors come in.

Manufacturers of the drugs misleadingly marketed opioid painkillers as safe and effective, with multiple studies tying the marketing and proliferation of opioids to misuse, addiction, and overdoses. Opioid makers like Purdue Pharma, Endo, and Teva are all accused of playing a role here.

As a group of public health experts explained in the Annual Review of Public Health, the companies exaggerated the benefits and safety of their products, supported advocacy groups and “education” campaigns that encouraged widespread use of opioids, and lobbied lawmakers to loosen access to the drugs.

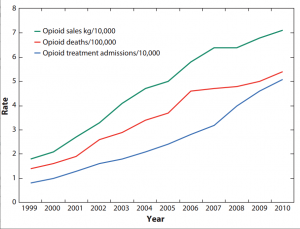

The result: As opioid sales grew, so did addiction and overdoses.

It’s not just that the drugs were deadly; they also weren’t anywhere as effective for chronic non-cancer pain as the companies claimed. There’s only very weak scientific evidence that opioid painkillers can effectively treat long-term chronic pain as patients grow tolerant of opioids’ effects — but there’s plenty of evidence that prolonged use can result in very bad complications, including a higher risk of addiction, overdose, and death. In short, the risks and downsides outweigh the benefits for most chronic pain patients.

While opioid manufacturers were the main culprits behind the marketing, distributors benefited as well — helping get the opioids out to pharmacies and consumers, making billions of dollars along the way.

Under federal law, these distributors are supposed to report suspicious orders of controlled substances, like opioids. But they often stood in the sidelines.

A previous investigation by the Charleston Gazette-Mail in West Virginia, for example, found that from 2007 to 2012, drug firms poured a total of 780 million painkillers into the state — which has a total population of about 1.8 million. Some of the numbers were even more absurd at the local level: The small town of Kermit has a population of 392, but a single pharmacy there received 9 million hydrocodone pills over two years from out-of-state drug companies.

With drug overdoses now tied to tens of thousands of deaths each year, different levels of government, as well as private groups and individuals, are now trying to hold both sides of the equation — the manufacturers and distributors — to account for the opioid crisis. That’s why Tuesday’s news of the charges against Rochester is a big deal: With criminal charges against a distributor, it shows a new step in that broader effort.

SOURECE ARTICLE: The federal government is escalating its action against bad actors in the pharmaceutical industry involved in the opioid crisis. By German Lopez@germanrlopezgerman.lopez@vox.com Apr 23, 2019, 2:42pm EDT